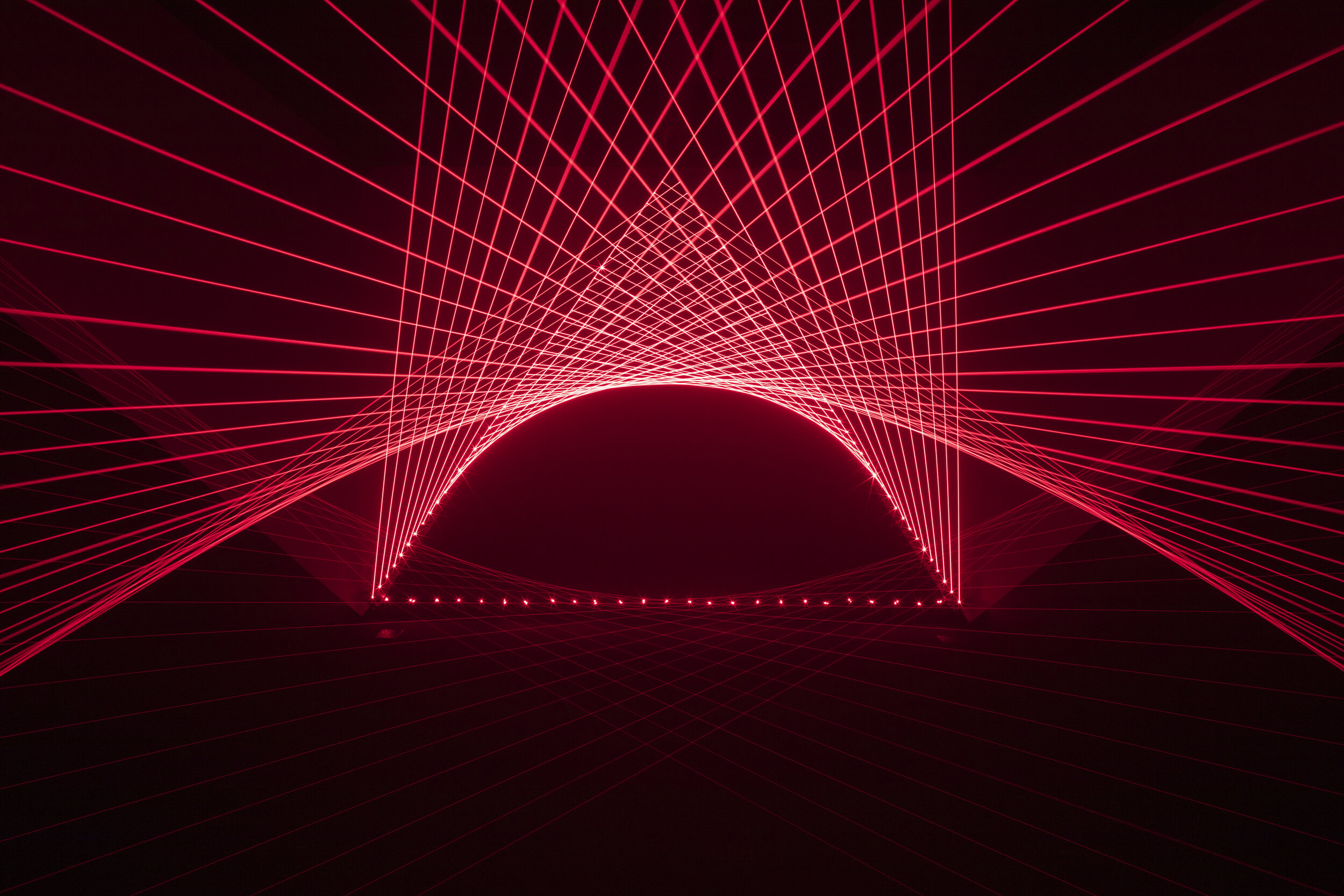

Crossbow 2016

3 Reflection holograms on Glass, 30x40cm each, edition of 2. Site-Scaled Laser Installation, Diode lasers, aluminum, electronics and haze. 7x 3 x 10meters

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca New York

Schreiber’s Solo Exhibition, Crossbow, organized by the Johnson’s Museum’s curator of Contemporary Art, Andrea Inselmann consisted of 2 rooms. The first installation titled Sprit Cabinet, contained 3 reflection holograms. The second room had a site-scaled laser sculpture, Crossbow.

Below is a review by Christopher J. Harrington

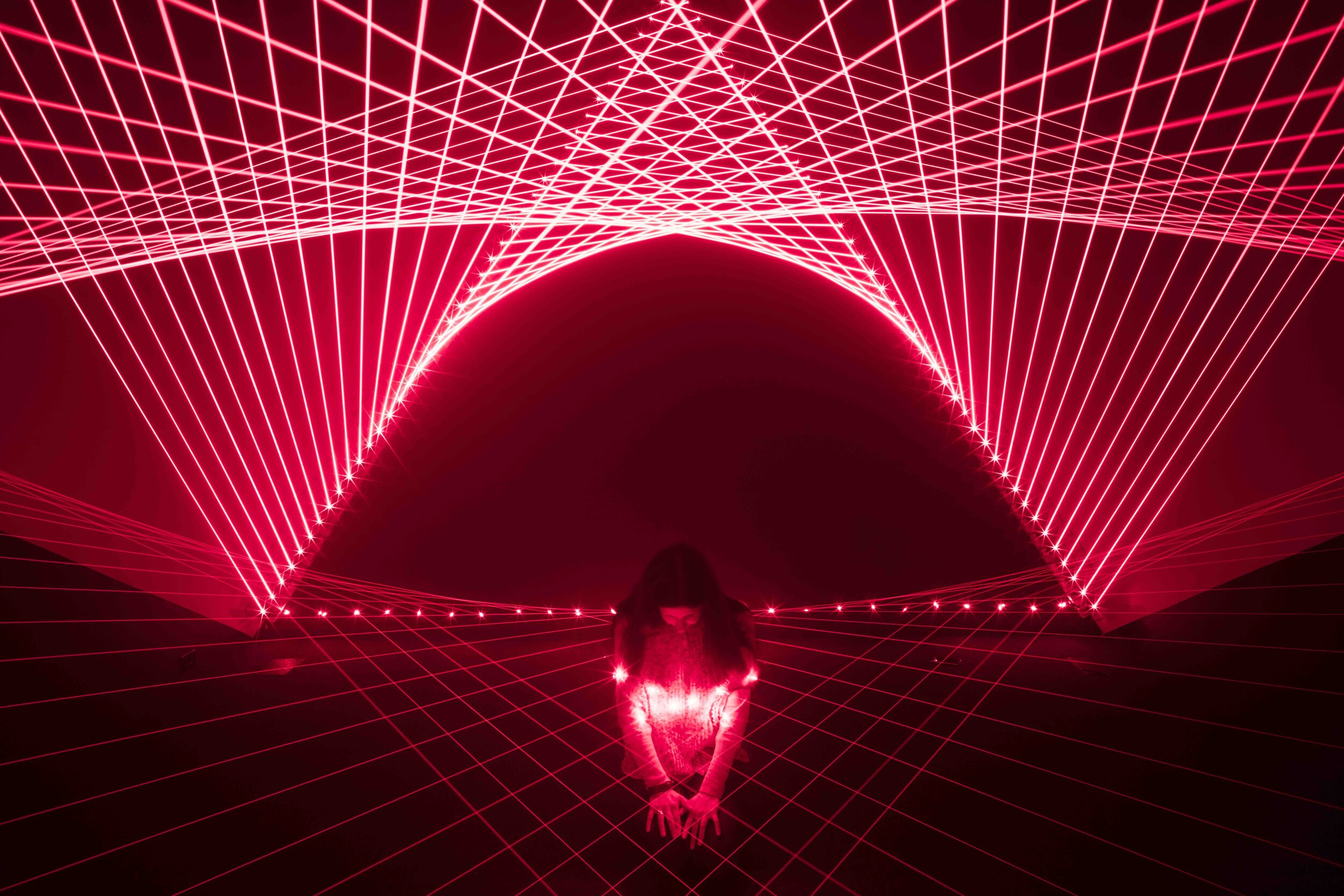

In a dark corridor, behind a strange corner, situated in a museum, atop a hill, there exists—temporarily—a passage into a sort of hallucinatory dimension that is caused by the architectural placements of numerous laser beams. Once the door is opened to this corridor, and you stroll on through to this illusory state, it may seem as if you’re walking straight towards the end of the universe, but alas, you’re not; a dark wall stops you in your tracks, and you’re turned around to face yet another geometric apparition.

Matthew Schreiber’s light installation Crossbow, meditating inanimately at the Johnson Museum of Art presently, serves as a sort-of vivos usu, representative of the artist’s long-tenured methodology and science-fiction worship. As a work of art, the installation dips its electromagnetic wings in varying academic templates and cultural behemoths, forging a brawny combo of learned trades, technical thrills, theoretical possibilities, and kitschy fantasy—very noble and very lively.

Schreiber served as chief lighting expert for the artist James Turrell for 13 long years. Turrell, the cowboy-ish light-mystic artist, is probably best known for his earthwork still in progress: the Roden Crater, located in Flagstaff, Arizona. The specifics of the piece involve the celestial, the spatial, and the financial. If you want to view the earthwork you have to complete a Turrell Tour, which involves seeing one of the artist’s pieces in 23 different countries. Yikes. Talk about science fiction.

Schreiber, on the other hand, bends towards the accessible. Crossbow is very much Coney Island freak show, Boston Museum of Science fantasy, and late ‘60s-era (think Star Trek, the original series) mysticism. And this is commendable. The best art is accessible, not governed.

You can’t help but think of the Greek philosopher Plato’s utterly mesmerizing allegory the “Myth Of The Cave” (part of the Republic) when baby-stepping around Schreiber’s installation. Plato’s allegory, which purposes the idea that human beings are much like prisoners—chained by their necks, unable to turn or look in any other direction, with an eternally lit fire to their backs projecting shadows on a cave wall in front of them—fits aptly with the illusions Schreiber’s lasers omit. The shadows are the only reality for the prisoners in Plato’s tale. In Crossbow, we have the chance to mediate on this metaphor, churning supposition like a science experiment. Plato used the metaphor to illustrate how humans lack the comprehension to grasp the metaphysical. Schreiber proposes we have some fun with these uncertainties.

Crossbow changes structural form constantly. Depending on where you stand in the space, the laser beams dictate the reality—or illusion—you experience. As a viewer, you have the ability to move around; freely dictating your semblance. You can use the space to propagate your own celestial hopes, and perhaps this is the true ulterior motive of the exhibit: to locate your own specific illusions to morph through, bend, compensate, and hope for. Like the stars that hover in the great night sky, Schreiber’s constellations are both representational and melancholy; the beams will turn off, but what about the impressions?

The fact that Crossbow is both whimsical and scientific—invoking movements, specific procedures, and pop-culture phenomena including Dadaism, Futurism, photorefractive keratectomy, space exploration, photocoagulation, Star Wars, films like Tron and Dark Star, books like Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics, and Carrie Fischer’s jerk boyfriend Aleksandr Petrovsky (he was the light artist in Sex and the City, remember)—altogether makes for an exhilarating experience that truly invokes the fundamentals in the pursuit of peace, love, and prosperity.

A brave nostalgia is at the ultimate crux of Crossbow, one that meditates on the long search for meaning in a corrupt society, adheres to the dreaming of proton pulses of distant galaxies, and acts as the cross-link to a brilliantly crazy stroll along a boardwalk in the perfection of a summer night. It’s all hoot—specific, expanding, and illusory. You can’t help but smile.