Platonic Solids 2006

Pipeline , Florescent Light, Tokyo Blue Filters 40x25x5.8 meters.

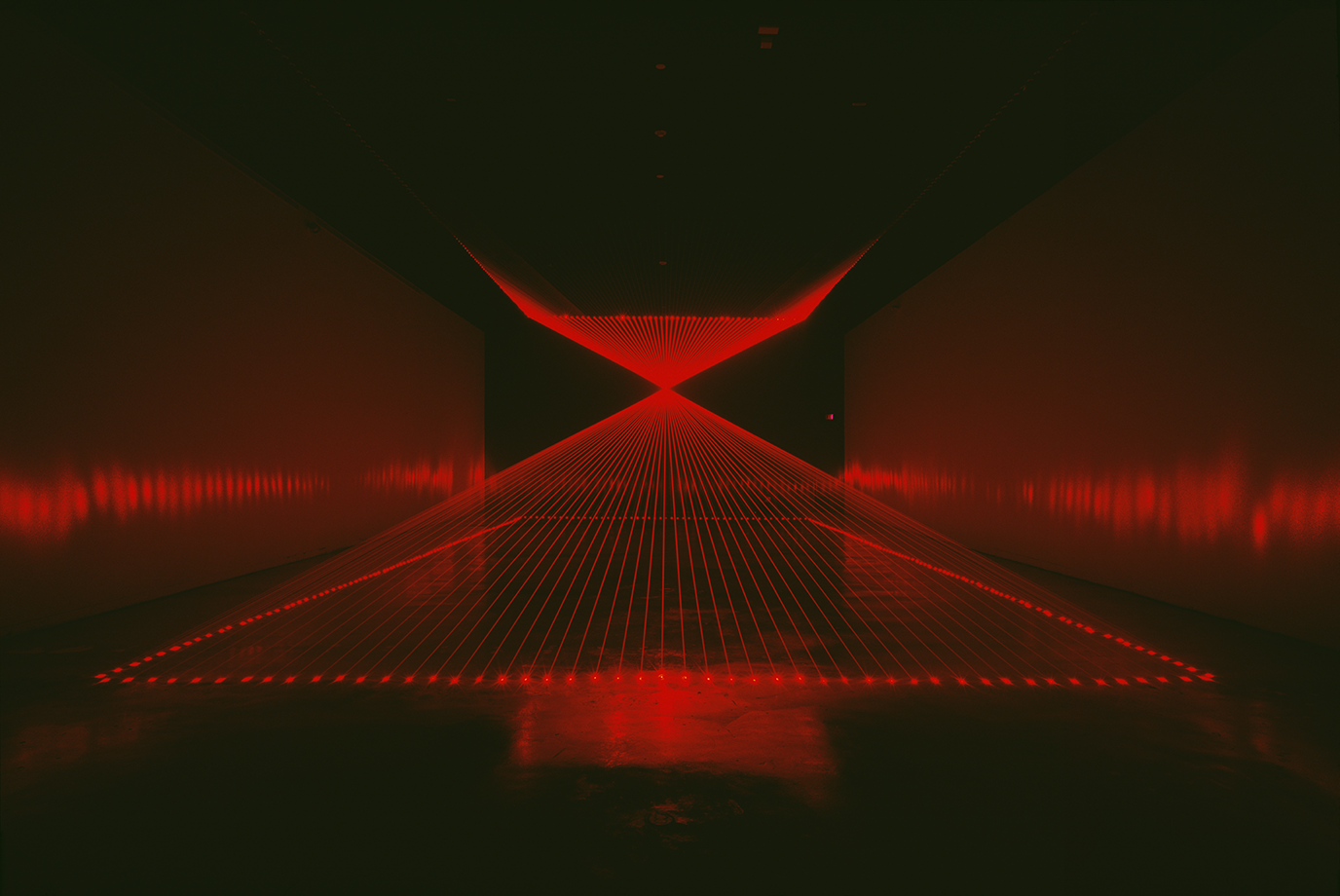

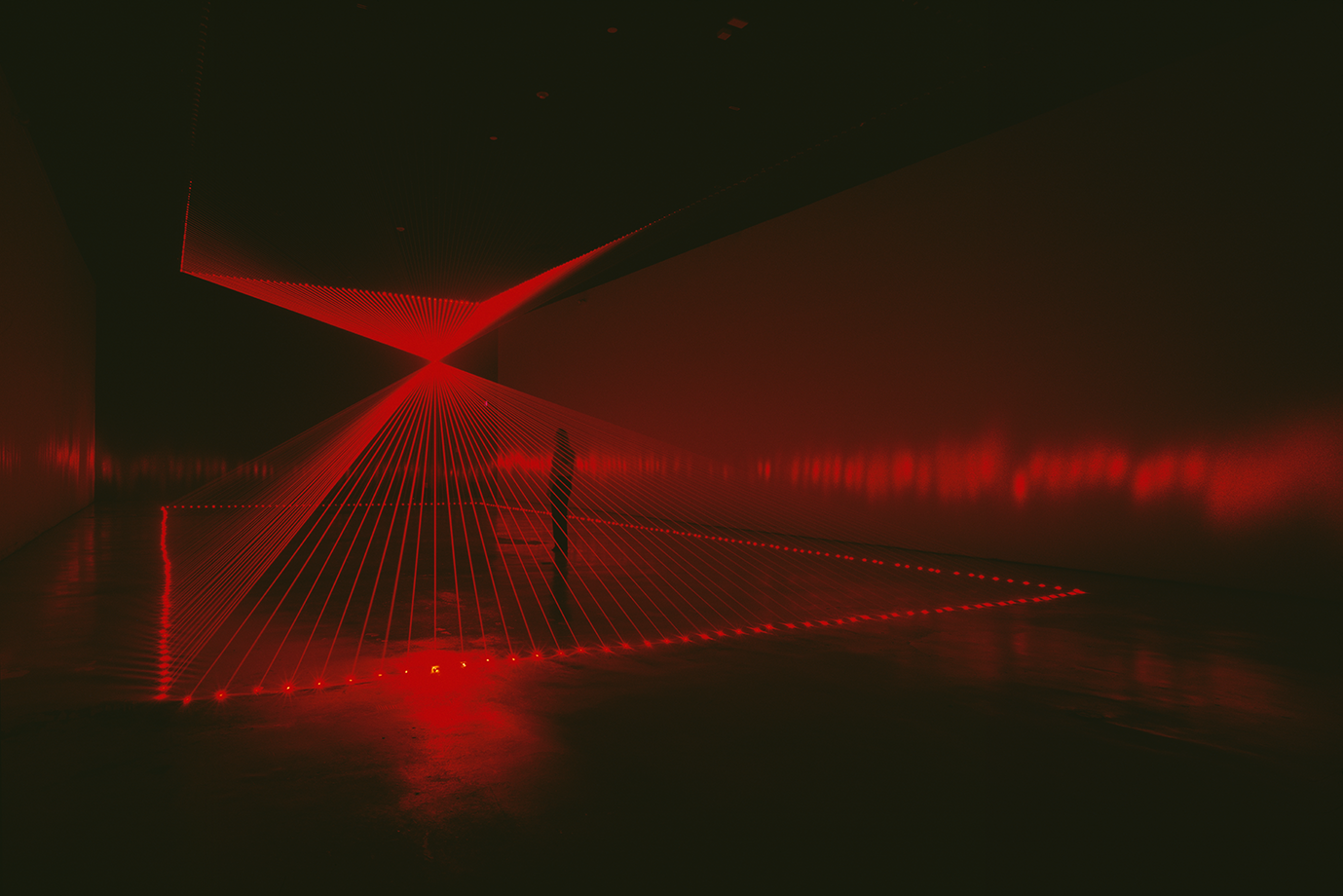

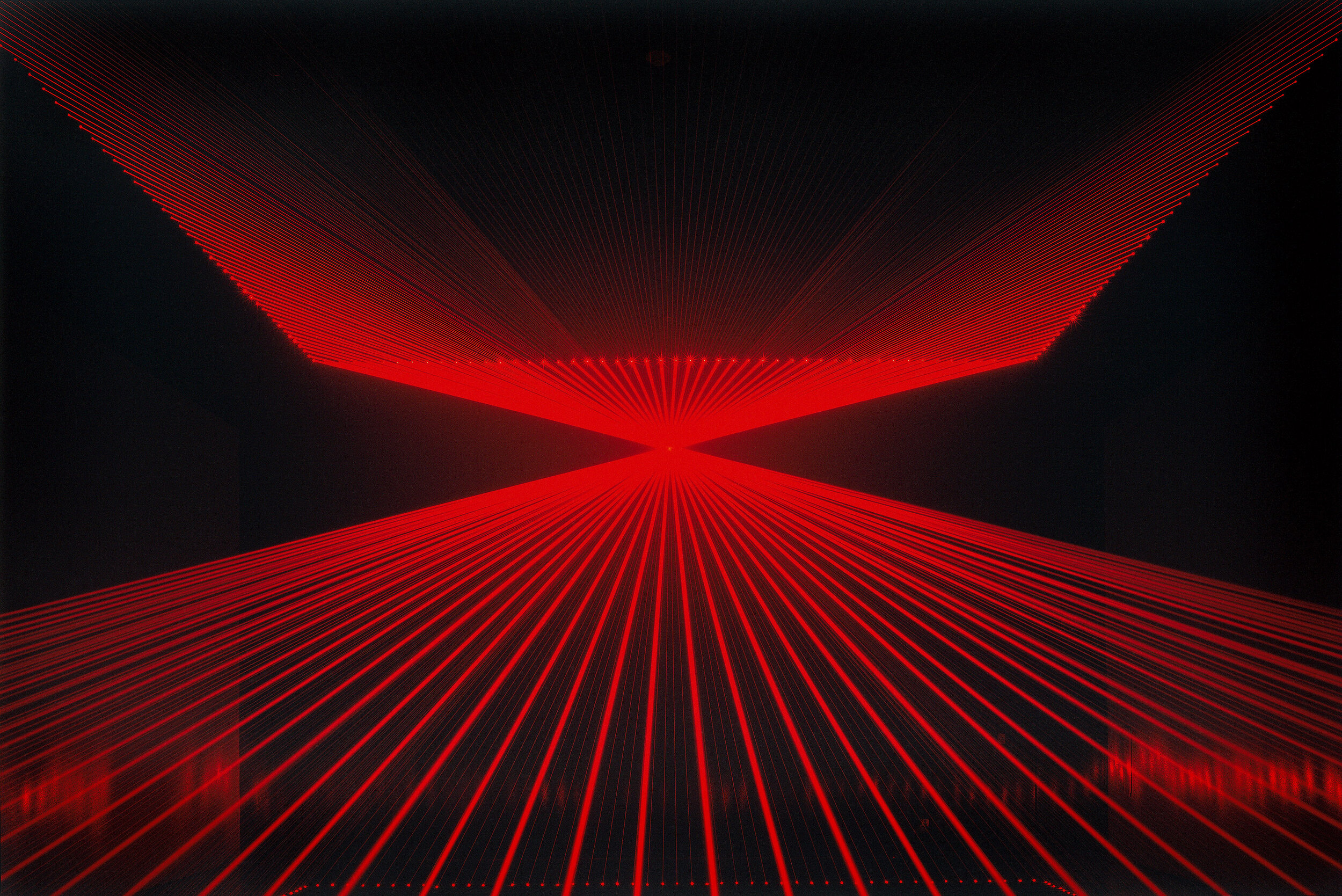

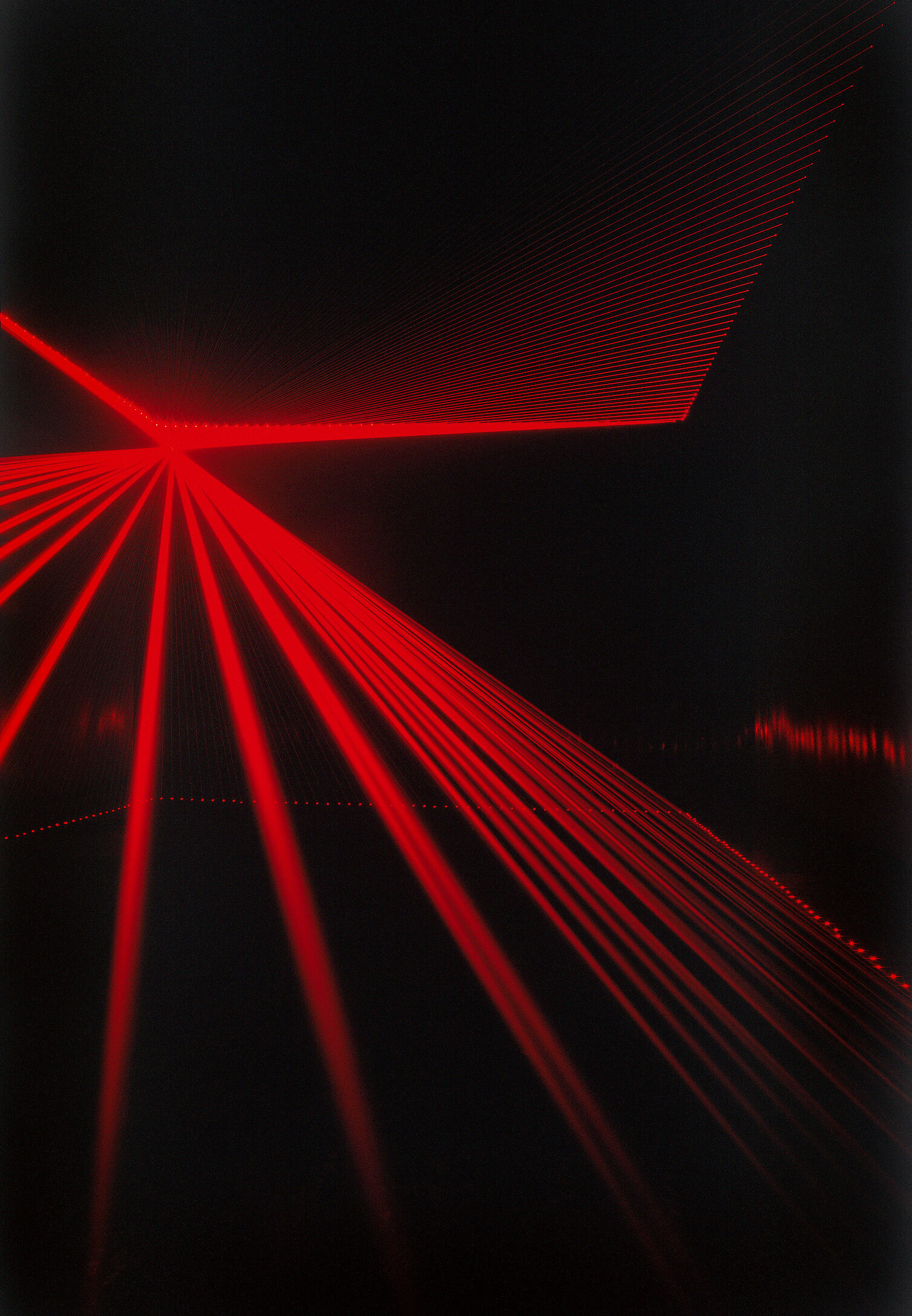

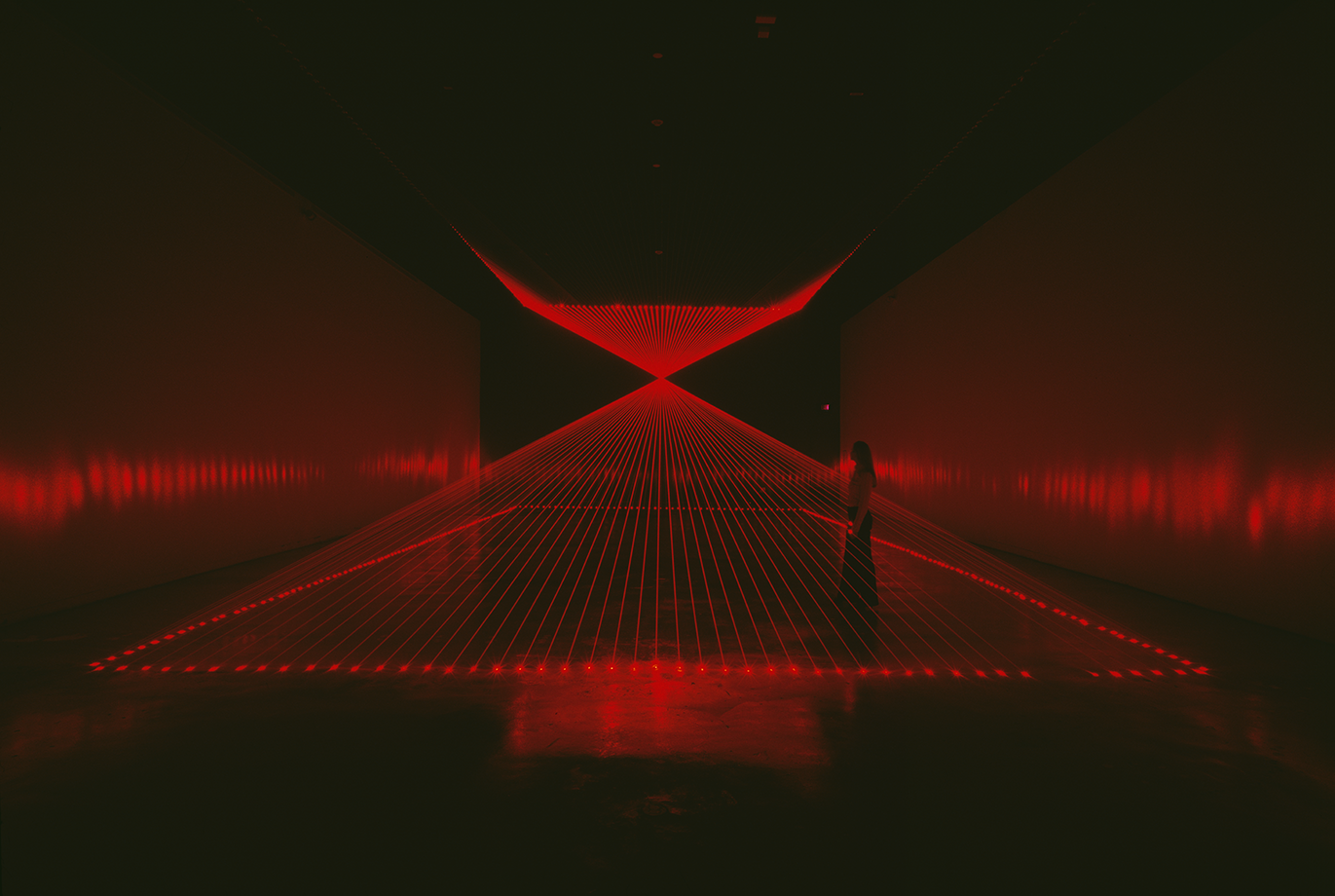

Garnet Cross, Laser Light, Electronics and Haze 15.5x23x5.8 meters.

NSU Museum Art Museum, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida

Schreiber’s Solo Exhibition, Platonic solids, consisted of 2 monumental immersive environments. The exhibition was curated by Annegreth Nill. A catalog was produced with an essay by Jenny Moore and photography by Florian Holzherr.

The catalog essay can be found below. And a full version of the catalog is linked within the artist biography.

A Light Fantastic by Jenny Moore

1. 500 Watts, Performance, 2003

2. Video Crystal, 2005

Matthew Schreiber’s explorations into the potency of light continue an artistic tradition that dates back at least to the beginning of the 20th century. While light in a representational form has served as a beguiling muse for centuries now, this elusive yet utterly familiar material was not freed from its depictional status until a handful of artists in the early 1920s, including Mary Hallock Greenewalt and Thomas Wilfred, fused color and luminescence in mechanical constructions that presented light as an artistic medium in and of itself. Minimalism and the Light and Space work that emerged from Southern California in the 1960s further explored the potential of light. James Turrell, Robert Irwin, and Dan Flavin, among many others, exploited it as a pure substance for investigations into the perceptual principles embodied by Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological theories. More recently, Olafur Eliasson and Spencer Finch have used both natural and artificial light to examine subjectivity in an age conditioned by simulation and Guy Debord’s concept of the spectacle. Although all of these precedents certainly inform Schreiber’s work, he chooses to take a different tack. For more than three years, he has employed fluorescent and laser light in the construction of spectacular geometrical forms that critique our increasingly mediated contemporary existence by looking back at a rather unexpected source – pop culture’s appropriation of one of our most profound experiences, our bodily engagement with light and space. His references are as multivalent as they are humorous. An encounter with any one of Schreiber’s works calls to mind the hallucinatory visualization of psychedelic art and liquid light shows; the laser light extravaganzas once featured in planetariums across the country; and the kitschy optical devices found in mall variety novelty stores. Most striking is a resemblance to the futuristic depictions of space stations and communal habitats so ubiquitous in science fiction films and television programs from the 1970s and ’80s.This aspect is key in deciphering the philosophical agenda of Schreiber’s work, which stakes its claim on a return of the real as manifested through his own brand of hand-made technology. For Schreiber’s sculptures and environments traffic in the kind of utopian visions that have fallen out of favor over the last two decades as our reality grows increasingly more simulacral and we depend to a greater extent upon virtual experiences to enthrall us. His works glorify a modern past, a time when technology offered the promise of a brighter future, a space quite literally illuminated by the brilliant aesthetic of uncluttered progress. And they reveal the startling fact that, despite our proficiency in manipulating infinitely more sophisticated technological systems, we still can’t quite get our heads around the fundamental principles of light perception.

500 Watts, 2003, and Black Light Circle, 2005, explore the potential for fluorescent light to evoke complex perceptual phenomena through the simple presentation of light in space. Installed in a performative act that took place over the course of two hours, 500 Watts (fig. 1) emerged as the form of a line arrested at various perpendicular points around a 360-degree rotation. The performance culminated with the illumination of the completed circle, the center of which was rendered almost imperceptible by the brilliance of the surrounding bulbs. It appeared as if one was staring into a black hole, depthless and formless. Unfolding in space and over time, the work illustrates that perception is as much a process as it is an act of optical recognition.

3. Black Light Circle, 2005

4. Rockne Krebs, Expo ’70, Osaka

The disorientation induced by 500 Watts is pushed even further in Black Light Circle (fig. 3). Consisting of ultraviolet “black lights” wrapped candy cane-style with strips of electrical tape and mounted to the wall in the shape of a radiant sun, the sculpture appears upon first glance as if shrouded in a fog. After several seconds, we come to realize that the haze is the result of an optical response to the light; it exists in our eyes, not in the physical space before us. Consequently, we become keenly aware not only of what we are seeing, but also of how we are seeing. Illusion becomes fact and fiction in this vibrant demonstration of Merleau-Ponty’s observation that “correct and illusory vision are not distinguishable in the way that adequate and inadequate thought are.”

5. Ontario, 2004 –2005

6. Platonic Solids, exhibition layout, 2006

Schreiber breaks new ground in an all but forgotten medium with his laser light works. Once touted as “a new visual art” that “pushes out the frontiers of art and enlarges the possibilities of creation,” lasers were a prominent feature in a variety of exhibitions throughout the late 1960s and early ’70s, organized in celebration of a widespread embrace of cutting-edge technologies for the creation of new kinds of art.3 Pioneers include Rockne Krebs and Robert Whitman. Krebs created one of the first large-scale laser installations for the Art and Technology exhibition at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan, which consisted of a variety of singular beams in different colors that were projected onto mirrors (fig. 4). Whitman’s Solid Red Line, 1967, comprised a single red beam marking a horizontal path across a gallery wall, then reversing and erasing itself.4 The fervor over laser light art rapidly died down, however, perhaps due to the suspect popularity of its increasing presence in rock concerts and light shows, and the medium seemingly became but a footnote in art history’s fixation on the more conceptual forms of art that followed. In a pedestrian context, lasers are ubiquitous today, appearing in the form of medical devices, bar-code scanners, low-tech pointers, and motion detectors, yet the discovery of them within an art context is hardly expected. Beholding the spectacular vision of hundreds of brilliant beams projected in a darkened gallery space, as one does with Schreiber’s work, proves that the potential of the medium as used in earlier works was just beginning to be tapped. Not only does he revive a lost medium, but he also renews our own sense of wonderment as we experience laser light in an entirely new way.

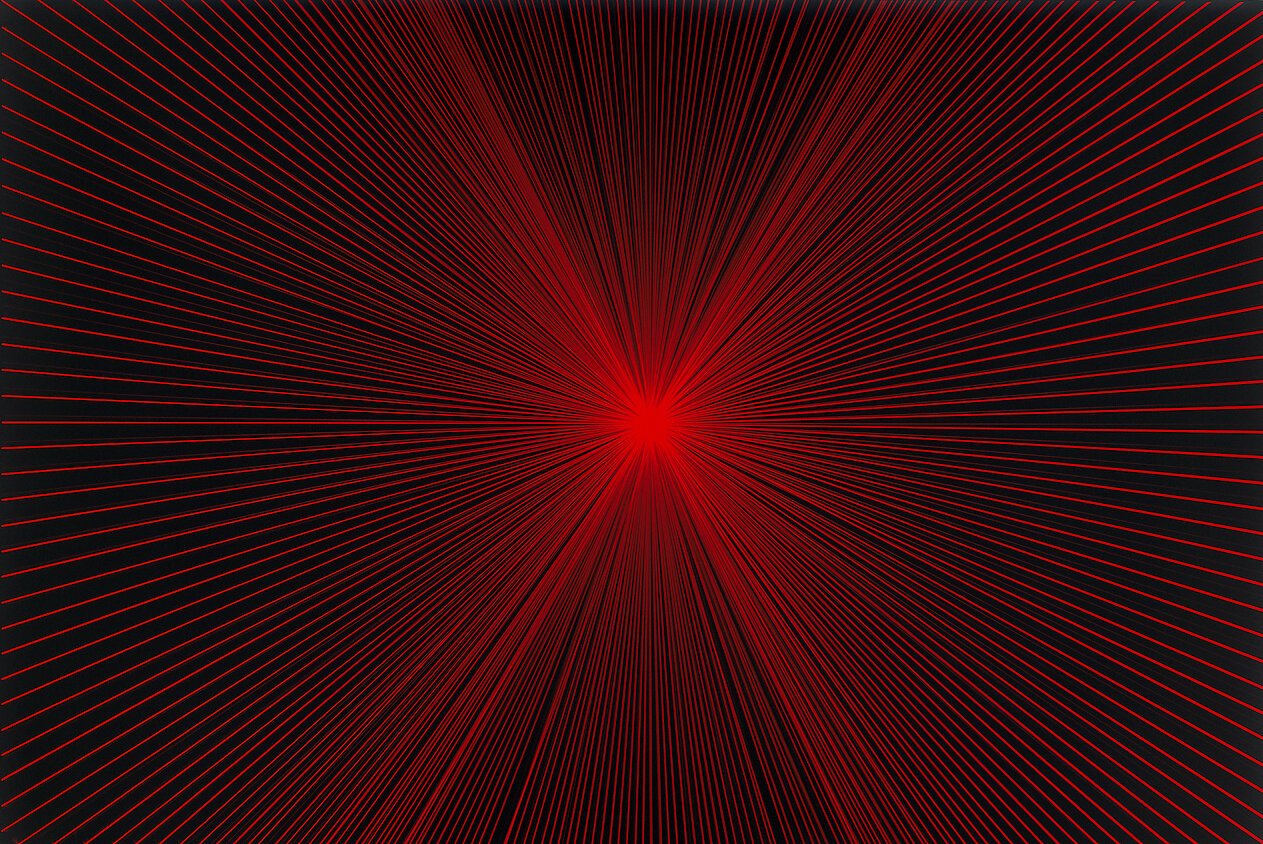

7. Pipeline (Tokyo Blue), 2006

Ontario, 2004–2005, (fig. 5) consists of four aluminum rings, 11 feet in diameter, spaced 30 feet apart in a darkened space. Each ring supports 48 lasers, all 192 of which are aligned to intersect at a precise point in the center of the structure, forming the shape of a cross that fans out at each end. Thin smoke periodically released into the room renders the cross solid, as if constructed by an array of bright red strings or thin, glowing metal rods. At one point, only the intersection of the beams is perceptible. Then the seemingly solid structure gives way to an arrangement of lines that appears like a brilliant starburst suspended in the center of the space. It hovers for several seconds – magical and fantastical – until, as the smoke clears, it too fades away. In apprehending Ontario, we find ourselves navigating a sculptural structure as well as the contradictory material properties of light, which are here rendered in every manifestation: visible and invisible, material and immaterial, enduring and ephemeral.

Platonic Solids, presented at the Museum of Art | Fort Lauderdale, is Schreiber’s most ambitious work to date. The two featured installations – Pipeline (Tokyo Blue) and Garnet Cross, both 2006 – incorporate distinct architectural elements of the Museum in a powerful display that creates a symbiotic dynamic whereby each work informs and reforms the experience of the other. Pipeline (Tokyo Blue) (fig. 7) is an installation of more than 200 eight-foot-long fluorescent light fixtures installed end-to-end vertically in groups of two along an interior wall of the Museum. The wall – one of the striking features of the Museum, designed by Edward Larrabee Barnes – takes the dramatic shape of a curve, 120 feet long, that encloses the front entrance and two floors of exhibition space. Covered by a deep sapphire-blue film that charges them with an almost ultraviolet appearance, the bulbs are placed at intervals along the wall, beginning above the base of a grand staircase that leads visitors up to the second-floor galleries, and continuing along the curved wall until it meets an opposing wall at the far end of the Museum. More fluorescent blue lights are attached to a progression of exposed galvanized steel studs placed along a line related to the outer wall, following an elliptical curve that results in a horn-shaped tunnel. The fixtures are spaced closer together as they approach the point where the curved wall meets the opposing wall, so that the area where the two curving lines meet creates a space of compression a quarter-inch wide by 19 feet tall (fig. 7). Impossible for a viewer to access, the space serves as the locus of the piece, drawing us into an extraordinary vortex of light, yet repelling us with its brilliant intensity and compressed space. As we navigate through the tunnel, we find ourselves in the midst of an exploration that is as much psychological as it is physical. We enter a state that can be likened to Kant’s notion of the sublime, in which the mind – faced with an experience beyond comprehension – alternates between an overwhelming sense of attraction and one of repulsion. The sensation lasts far longer than our presence in the tunnel, for once we step outside its vibrant core, we succumb to the effect of afterimage, which washes everything subsequently viewed in a pale orange hue.

Pipeline references elements of art historical precedents as well as the aesthetics of such science fiction films as the landmark 2001: A Space Odyssey and the cult classic Tron. The experience of fluorescent light as a self-referential sculptural element, first explored by Dan Flavin in his brilliant icons and site-related installations (fig. 8), and its power to elicit distinct emotional responses as demonstrated in Bruce Nauman’s altogether unsettling corridors (fig. 9), is played against a more populist recognition of “space” activated with light. Viewers are pulled along a trajectory of increasing intensity in a sensation not unlike that which we have come to recognize from movie clips and virtual reality displays. Yet here, the forces are actual. Our physical movement through the tunnel and our perception of light is real; it is not manifested by digital technology or controlled in a virtual environment. Schreiber’s installation succeeds in appropriating virtual reality devices used to convey motion (and, by default, progress) by going back to the concrete means, such as curved tunnels and forced perspectives, that initially induced this kind of sensation. Thus the work is simultaneously familiar and frightening, thrilling and nostalgic. We feel as if we have been here before, even if we never have.

8. Untitled, Dan Flavin, 1970, Dia: Beacon

The perception of volume, space, and light in Pipeline prepares viewers for an altogether different experience of these elements in Garnet Cross. We approach the installation through a dark corridor that opens up into a large rectangular gallery. Three hundred red lasers, mounted on a rectangular aluminum frame measuring 50 feet by 25 feet and affixed to the ceiling, are directed at a point approximately nine feet high in the center of the gallery. The resulting form is a spectacular, monumental set of pyramids, one inverted over the other, attached to each other at their tips. Like Ontario, Garnet Cross is a geometrical shape, constructed with thin beams of light, that appears to be completely solid.

There is an incredible moment of bewilderment, apprehension, and exhilaration when we first approach the form. Although reason allows that the beams of light can be crossed, the body, nonetheless, proceeds with caution as it enters into the structure, as if certain that they present a physical barrier to an interior space. This apprehension yields to a time of rapturous exploration. Properties of reflection and absorption, materiality and immateriality, are investigated by crossing into and through the beams. Perception is heightened with an awareness of how one moves in relation to and reacts against the interplay of light on the body and the body in space. At such a large scale, the contradictory material qualities of light become increasingly apparent. While from a distance the form appears solid, upon closer observation it shimmers and disintegrates, as swirls of smoke crossing through the light beams produce the effect of a moiré pattern (fig. 10). A trace of the artist’s hand is discerned at points where singular beams are not set in perfect alignment with the rest. It is here that the hard-finish of technology gives way to a previously unseen human presence, revealing the fact that Schreiber constructs all of his installations by hand; none are mechanically fabricated or aligned with the aid of computers.

9. Green Light Corridor, Bruce Nauman,

10. Garnet Cross, 2006

Once we gain access to the interior of the structure, there is no doubt that we have entered a distinct volume of space, one that is experienced quite differently from the environment outside the form. The palpable sensation of density inside Garnet Cross relates back to that felt in Pipeline, although here it is achieved through the projection of brilliant beams that have no concrete physicality. Our interaction – walking through and among or crouching under the beams of light, experimenting with space and perceiving anew – becomes an integral part of the piece, rendering the work both sculptural and performative. Ultimately, we become conscious of being caught in a place of virtuality that is as real as our presence in it and as evanescent as the most indeterminable of sensations.

“Shall we…use the new art as a vehicle for a new message [and] express the human longing which light has always symbolized, a longing for a greater reality, a cosmic consciousness, a balance between the human entity and the great common denominator, the universal rhythmic flow?” – Thomas Wilfred It has been widely acknowledged that we have now crossed the threshold of an entirely new world of information, communication, and perception that is singularly grounded in the terrain of telematic technology and cyberspace. Schreiber responds to this paradigmatic shift by offering works that enable us to participate both physically and conceptually in a reevaluation of our relationship to the fundamental elements upon which much of our reality, up to this historic point, has been founded. Although it remains to be seen to what end this technological revolution will serve, for the time being we can revel in the notion that the future might yet be as spectacular as the luminous beauty of Schreiber’s fantastic lights.

1. Kim Levin first used the phrase “modern past” in her essay “Lucas Samaras: The New Reconstructions,” printed in the exhibition catalog Samaras: Reconstructions (New York: Pace Gallery, 1979).

2. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (New York: The Humanities Press, 1962), 297.

3. Richard J. Boyle, Laser Light: A New Visual Art (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum, 1969), 12.

4. Lynne Cooke, Robert Whitman: Playback was retrieved from

<http://www.diacenter.org/exhibs/whitman/playback/essay.html> on June 12, 2006.

5. Thomas Wilfred, “Composing in the Art of Lumia,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol.VII, No. 2 (December 1948): 90. Quoted by Willoughby Sharp in “Luminism and Kineticism,” Minimal Art: A Critical

Anthology, ed. Gregory Battcock (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), 321.